From Landmines to Lung Disease: How Rats Are Saving Lives

The same rats that once cleared minefields are now helping doctors detect a disease that kills more people than HIV or malaria.

A Surprising New Mission

Apopo, a Tanzania-based non-profit, has been training rats for over 20 years. Originally, these rats saved lives by detecting landmines, but now the company is turning its attention to an even bigger killer: tuberculosis.

“Tuberculosis is a huge killer in Sub-Saharan Africa and around the world,” says Lily Shallom, Communications Officer at Apopo.

While all but unheard of in the United States, in 2015, the World Health Organization announced that tuberculosis kills more people every year than HIV/AIDS or malaria. Around 10.4 million people fall ill with the disease yearly, and three million of those cases go undiagnosed.

“All of those people who go undiagnosed not only aren’t getting the treatment they need, but they’re also spreading the disease to others,” says Shallom. “Without treatment, patients often die, but before they do, they can spread the disease to as many as 15 other people within a single year.”

From Battlefields to Clinics

Apopo has been training rats for a long time. In the mid-90s, the organization pioneered using the African giant pouched rat to detect landmines. The rats are smart and easy to train, using their potent sense of smell to detect explosives. They’re small and agile, making them perfect in the field as they’re too light to trigger a landmine once they discover it. Using rats as mobile landmine detection units was once radical, but it is now proven. Over the years, their rats have found more than 100,000 landmines and other explosives, and are currently hard at work in places like Angola, Cambodia, and Mozambique.

Sniffing Out a Hidden Killer

Now, the organization uses the same training methods and approach for tuberculosis. When the rats can open their eyes, they are trained to detect tuberculosis by smell and rewarded with food when they do. A lineup of 10 samples is placed in front of a rat, who sniffs each one. To indicate a positive sample, the rat sticks its nose through a small hole and holds it there for 3 seconds.

“We’re not sure what exactly they’re able to smell,” Shallom says. “But we know that tuberculosis gives off specific volatile organic compounds and that those are the source of the scent they detect.”

How It Works

It’s a little gross, but here’s how it works. Sputum samples, basically hacked-up phlegm, are collected from patients at clinics and taken to one of Apopo’s labs. These samples go through sputum microscopy, a fancy way of saying that a person looks for signs of the disease under a microscope. It’s this step that results in so many missed diagnoses, as there are many ways the human eye can miss signs of a bacterium. And, it’s here where the rats start to shine.

After going through sputum microscopy, the samples are passed off to the rats and their handlers. One rat will screen about 100 samples in as little as 30 minutes, a task that takes humans with a microscope around four days. If the rats indicate a sample contains tuberculosis, the sample is sent back through for another round of microscopy to ensure the diagnosis is correct. So far, they’ve found that this method detects 40 percent more cases than just a single pass of sputum microscopy, and the rats have spotted 1,677 cases that would have otherwise gone undetected.

Challenges and Limitations

The rats have their limitation, though, and right now they are classified as ‘for research use’, which means they’re only allowed to be used as a secondary screening measure along with a World Health Organization-endorsed confirmation test like LED fluorescence microscopy. And, as good as they are at sniffing out samples with tuberculosis, they’re unable to indicate samples that are disease-free. So, research continues, and as you read this, rats are sniffing their way through thousands of samples at Apopo’s labs in Tanzania, Mozambique, and Ethiopia. In 2017 alone, they screened over 61,928 samples from over 100 hospitals and clinics.

When Technology Falls Short

Of course, all this isn’t to say that humans haven’t created an amazing high-tech way to detect tuberculosis. The GeneXpert MTB/RIF is a cartridge-based machine that can quickly diagnose tuberculosis and its antibiotic sensitivity. By all accounts, it’s an amazing machine, and in 2010, the World Health Organization endorsed the device for field use in tuberculosis-endemic countries. But, as good as all that tech is, sometimes a rat is just better suited to the environment.

“The GeneXpert is a great machine,” Shallom said. “But, it costs around $30,000, requires a consistent electrical supply, and each cartridge costs $10. Oh, and they need to be placed in an air-conditioned room. That’s not really realistic around here.”

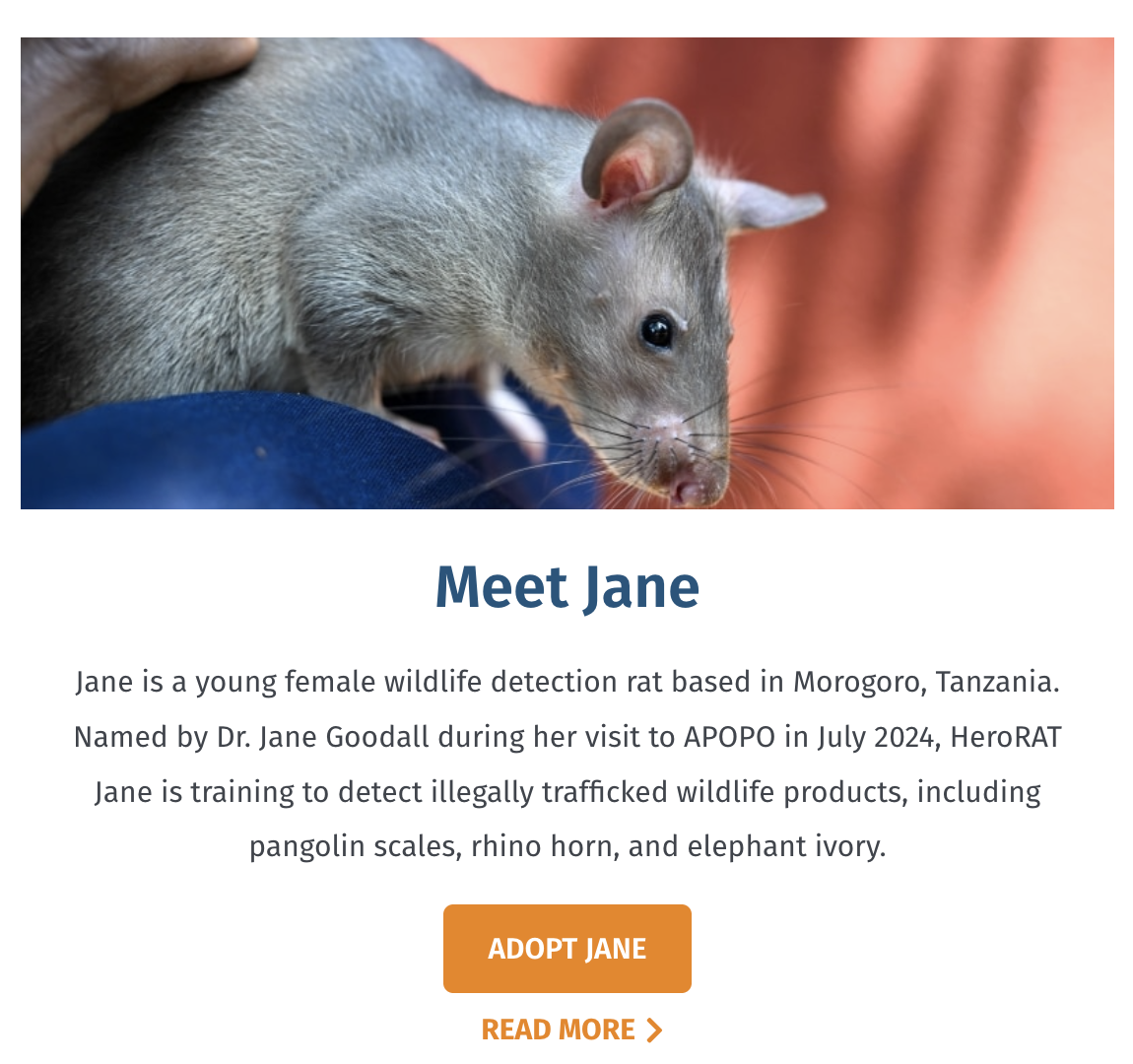

Adopt a Hero Rat

If you want to support Apopo’s work, you can even adopt a rat from their website. Each adoption helps fund the training and care of these unlikely heroes—tiny creatures making a very big difference in the fight against one of the world’s deadliest diseases.